Banned from school, Afghan girls turn to seminaries

Kabul, Afghanistan (AFP):

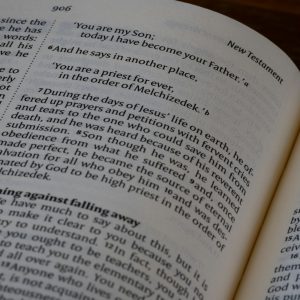

In a madrassa (religious school) in the Afghan capital, rows of teenage girls sit reciting verses of the Holy Quran under the watchful eye of a religious scholar.

The number of Islamic schools has grown across Afghanistan since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021, with teenage girls increasingly attending classes after they were banned from secondary schools.

“We were depressed because we were denied an education,” said 16-year-old Farah.

“It’s then that my family decided I should at least come here. The only open place for us now is a religious school.”

Most of them are memorizing the Arabic verses of the scripture. Some of them are also taught the meaning and explanation of the Arabic text in their local language.

In Kabul and in the southern city of Kandahar, the numbers of girl students has doubled since last year.

Education deadlock

The Taliban government adheres to an austere interpretation of Islam.

Rulings are passed down by the reclusive supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada and his inner circle of religious advisers, who are against the secular-Western model of education for girls and women.

Authorities in Kabul have given several excuses for the closure of girls’ schools — including the need for segregated classrooms and Islamic uniforms, which were largely already in place.

The government insists schools will eventually reopen.

Education is the main sticking point behind a deadlock with the international community, which has condemned the stripping away of freedoms for women and girls.

No country has recognised the Taliban government, which is battling to keep afloat an economy where more than half the population face starvation, according to aid agencies.

Hosna, a former university student studying medicine, now teaches at a madrassa in Kandahar, reading verses of the Quran to a class of more than 30 girls.

In the impoverished country which had all international aid withdrawn when the Taliban took over, most madrassahs are located in old buildings, with small classrooms and often no electricity.

What attracts poverty-stricken families to send children to the madrassahs is the fact that students attend classes for free.

Friendship and distraction

“Given the present conditions, the need for modern education is a priority,” said Abdul Bari Madani, a scholar who frequently appears on local TV to discuss religious affairs.

“Efforts need to be undertaken so that the Islamic world is not left behind… letting go of modern education is like betraying the nation.”

Niamatullah Ulfat, head of Islamic Studies at Kandahar province’s education department, said the government is “thinking day and night about how to establish more madrassas in the country”.

“The idea is that we can bring the new generation of this country into the world with good training, good teachings and good ethics,” he said.

Yalda, whose father is an engineer and mother was a teacher under the ousted US-backed regime, was top of her class at her old school, but still shines at the madrassa and has memorized the Koran within 15 months.

“A madrassa cannot help me in becoming a doctor… But it’s still good. It’s good for expanding our religious knowledge,” the 16-year-old said.

The madrassa, on the outskirts of Kabul, is divided into two blocks — one for girls and the other for boys.

Several girls said that attending a madrassah does provide some stimulation — and the chance to be with friends.

“I tell myself that some day the schools might open and my education will resume,” said Sara.

If not, she is determined to learn one way or the other.

“Now that there are smartphones and the internet… schools are not the only way to get an education,” she added.